To Win a Quick Victory

A Continent of Boundless Optimism

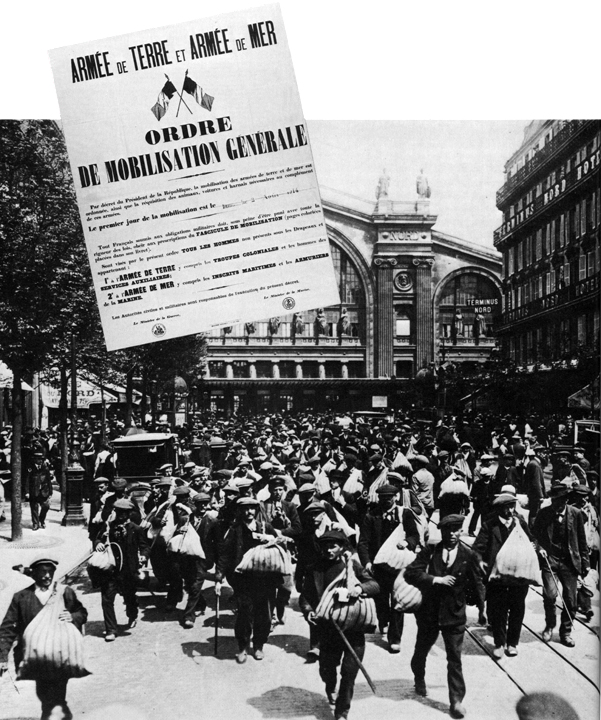

French conscripts at the Gare du Nord in Paris on their way to join

their units on mobilization.

INSET French mobilization poster.

War had been declared, but the armies had yet to march. First came mobilization and deployment, lasting a fortnight or more; a titanic administrative task, planned by the general staffs of Europe for decades. In those first weeks of August several million men passed through the barracks, exchanging civilian clothes for rough new serge and hard new boots, drawing rifles and equipment, and marched off to entraining stations. Following detailed timetables the railways rolled the armies towards the frontiers to meet each other in battle. The women and children and old men cheered the soldiers away; the soldiers leaned laughing out of carriages that bore chalked slogans like 'To Berlin' or 'To Paris'.

Behind the frontiers the units of each armed mass slotted into place: companies, battalions, brigades, divisions, army corps and armies. They rejected a Europe in transition from a life based on agriculture to one based on industrial technology. Precision engineers had designed and made the machine gun and the quick-firing held gun such as the French 75. The heavy artillery, especially the Krupp 420-millimetre and Skoda 305-millimeter siege howitzers, was the product of the metallurgical scientist and giant steel industries. A chemical industry developed in the last 40 years supplied the explosives and the smokeless powder that propelled the shells and bullets. A new invention, the radio, supplemented the telephone and telegraph, each cumbersome set filling a horse-drawn cart. Airpower too was making its debut in war, each army deploying flimsy machines for reconnaissance; Germany had her giant airships too, the 'zeppelins' named after their creator. The recently dawned age of the internal-combustion engine was represented by staff cars, motor cycles and a relatively small number of motor trucks. Yet, once away from the railheads, the armies would depend for movement like their predecessors through history on hooves and feet. The farms of Europe yielded up millions of horses to haul supply wagons and ambulances, to pull the field guns and their limbers, and mount the cavalry. And - except for the small all-professional British army, which drew the bulk of its recruits from industrial towns - the majority of the rank and file came from the farms as well; tough peasants inured to hardship, jealous of their land.

The soldiers leaned laughing out of carriages that bore

chalked slogans like "To Berlin'' or "To Paris''.

Almost all pre-war thinkers had agreed that the war would be short, decided in the first great encounter battles. Only a Polish banker named Bloch, in his book Is War Now Impossible?, had predicted a long war of attrition fought by armies locked into trench systems. Each general staff had therefore planned to win a quick victory. The Austrians meant to crush the Serbs and then join their German ally in smashing the Russians. The Russians intended to advance on Berlin via East Prussia while their ally France was defeating the bulk of the German army. The French, under their Plan 17 (the 17th annual revision) proposed to attack across the Franco-German frontier into Lorraine with all forces united 'whatever the circumstances', and shoulder their way to the Rhine in a phalanx of four armies. The British Expeditionary Force (known as the BEF), by pre-war arrangement, deployed south of Maubeuge, near the Belgian frontier, ready to advance as part of the flank guard on the left of the French offensive. And the Germans had the Schlieffen Plan. Seven German armies, together 1,500,000 men, the most enormous attacking array ever seen in history, were to advance against the French, while only a single army was left to face the Russians in the East. Five of these armies were to carry out a vast wheeling movement, pivoting on Verdun, that would sweep through Belgium, completely outranking the powerful defences along the Franco-German frontier; down to the River Seine, which would be crossed west of Paris, and then swing eastwards to corral the French forces against their own frontier defences. The French, constantly outranked and finally taken in the rear, would be certain to face total destruction.

'The women and children cheered the soldiers away'

- this German photograph expresses the exhilaration

of the belligerents as the war began.

First the gate to the Belgian plain, Liege and its circle of 12 forts, must be unlocked so that Kluck's First Army of 320,000 men, the outermost army in the German line, could pass through. On 5 August, when mobilization had hardly begun, a special German assault force tried to take Liege by a coup de main. But General Gérard Leman, the fortress commander, was determined to resist to the end. The guns in the steel cupolas of the subterranean forts and the rifles and machine guns of the Belgian infantry in between shattered the East German attacks in a terrible demonstration of what modern firepower could do to brave men. On 10 August the Germans brought up their heavy Krupp and Skoda siege mortars, crushing the Belgian forts one by one like beetles. The last fell on the 16th, the day German mobilization and deployment were completed. Two days later Kluck's First Army set of towards Brussels, trampling over the Belgian army's gallant but unavailing resistance.

On 14 August the French had begun their own advance under Plan 17 across the Franco-German frontier into Lorraine. Before the war French military theorists had preached that brave infantry could overcome the firepower of the defence by sheer élan and cran ('guts'). The French therefore lacked heavy mobile artillery, while their held artillery had been taught to support the infantry's onward rush, not prepare the way for it. Now, in red trousers and blue coats, with bugles blaring and colours dying, the French army tried to fulfil this romantic military dream. The wooded, broken hills of Lorraine provided the Germans with perfect defensive country. Day by day well-sited machine guns and artillery slaughtered the advancing French. On 19-20 August, in the twin battles of Morhange-Sarrburg, Plan 17 finally broke down, for all the courage of French officers who, leading their men to the charge, 'thought it chic to die in white gloves'. By now the Schlieffen Plan was fast unfolding. On the 20th Kluck's geld-grey columns trudged for hour upon hour through the Belgian capital of Brussels before swinging southwest towards the French frontier. Behind them the German troops left a trail of atrocity - burned villages, shot civilians. On the 25th they set ablaze the ancient city of Louvain with its priceless library of medieval manuscripts. At Dinant on 23 August von Hausen's Saxons shot over 600 men, women and children in the main square. The atrocities were supposed to serve a purpose - to crush any spirit of resistance among the hapless Belgians. lnstead they roused the anger of Germany's enemies, and besmirched Germany's name before the world.

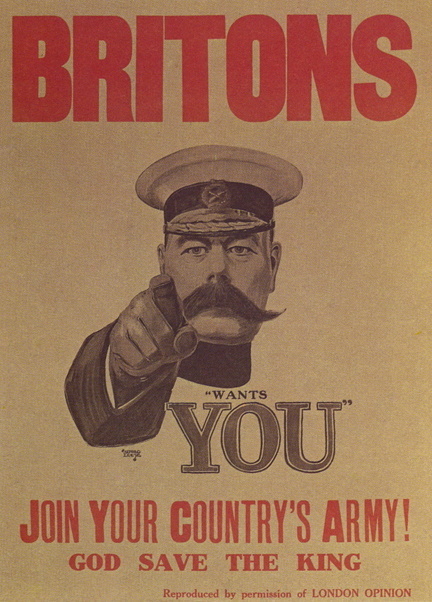

This famous Kitchener recruiting poster of 1914 was the most

successful of all those produced by the Parliamentary

Recruiting Committee. The original drawing by Alfred Leete

is in the Imperial War Museum, London.

For General Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, the cumulative signs of the enormous strength of the German right wing and its extent so far west-wards were alarming indeed. Joffre reckoned that since the enemy was strong on his two flanks in Lorraine and Belgium, he must be weak in his centre, in the Ardennes. He decided to hew the German wheeling arm off at the joint by attacking here. On 22 August this French offensive too collapsed in bloody loss under the impact of German heavy and light howitzer fire. The Germans had made themselves strong everywhere by employing reservist divisions in the line, contrary to French practice. As General Charles Lanrezac's Fifth French army was forced back from the town of Charleroi by the weight of two German armies, and Kluck's First Army curled round Lanrezac's bank and headed for the British Expeditionary Force, the appalling danger to the left of the whole Allied line became apparent. Field-Marshal Sir John French, the British Commander-in-Chief, was actually proposing on 23 August to continue his advance in conformity with previous French plans when his liaison officer with Lanrezac arrived to tell him that his French neighbour was in full retreat. So instead the BEF prepared to fight a defensive battle against Kluck amid the slagheaps and red-brick mining villages south of Mons.

Kluck himself had no idea of the exact whereabouts of the British because his reconnoitering cavalry had been unable to penetrate the skillful British cavalry screen. Instead of outranking the heavily outnumbered British on their left, he blundered into mounting a piecemeal frontal attack on one of the two British corps. The 23rd was a Sunday; all over the coming battlefield the church bells were summoning the devout to Mass as the British army prepared for its first battle on European soil since Waterloo. It was a day when more peacetime illusions were shed. At least one German reservist had expected the British to be dressed in bearskins and scarlet; instead he saw 'a man in a grey-brown uniform, no, in a grey-brown golfing suit with a flat-topped cloth cap. Could this be a soldier?' The Germans soon learned. Deployed behind the Mons-Condé canal, each infantryman getting of up to 15 aimed shots a minute, the superbly trained all- regular British stopped the German mass attacks in their tracks. The following day, with Kluck at last swinging wide round its left flank and the French on its right in full retreat, the BEF slipped away. It was the beginning of 'the Retreat from Mons'; a retreat interrupted only by another successful defensive time-winning battle at Le Cateau on 26 August.

German soldiers and artillery passing through Brussels in August 1914.

Now the full weight of the German swinging arm was felt all the way from Flanders to Lorraine. With the Allied armies stumbling back in disarray, the Schlieffen Plan seemed to be fulfilling every hope of its inventor.

Only on the eastern front had German calculations gone astray, for the Russians had sprung a surprise: far from being so slow to mobilize that Germany would have time to defeat France first, they began to invade East Prussia on 17 August. Their First Army under Pavel Rennenkampf (a general of German extraction) lumbered through the dense conifer forests and bleak meres of the Masurian Lakes region towards Königsberg, taking Gumbinnen and Insterburg. Further to the southwest the Russian Second Army under Alexander Samsonov advanced on Allenstein. The trim Teutonic townships of East Prussia trembled with an ancient fear of Slav hordes pouring out of the barbaric east. German roads too began to carry their sad burden of refugees. On 20 August, von Prittwitz, commander of the heavily outnumbered German Eighth Army, lost his nerve and telephoned Moltke to say that he was ordering the abandonment of East Prussia and a general retreat behind the Vistula. That day too Moltke learned that the Austrians, who had invaded Serbia on the 12th, had been flung back by the Serbs with heavy loss; a tragi-comic denouement to Austria's eagerness to force a war on Serbia during the July crisis.

To replace Prittwitz, Moltke called out of retirement the 68-year-old Paul von Hindenburg, giving him General Erich Ludendorff, a restless, aggressive soldier, as his Chief of Staff. On 23 August, the day of Mons, they arrived at Eighth Army headquarters at Marienburg, only to discover that Colonel Max Hoffmann, the able operations officer, had devised a daring plan for destroying both Russian armies; a plan which they immediately approved for action.

Samsonov's Second Army, its 200,000 men lacking field kitchens in a country of barren heath and forest, was crawling wearily forward under a broiling sun towards Allenstein - and getting further and further out of touch with Rennenkampf 's First Army over to its right. Thanks to Russian indiscretion in using the radio en clair without enciphering, the German command enjoyed an accurate picture of enemy dispositions. Leaving only a single cavalry division facing the sluggish Rennenkampf, they concentrated their entire available strength by rail against Samsonov. On 26 August Hindenburg and Ludendorff struck home at Tannenberg, their traps utterly outfighting the bewildered, hungry and tired Russian peasant mass. By the 30th they had gained one of the great victories of history, taking 120,000 prisoners and completely destroying Samsonov's army. Samsonov shot himself in the depths of a wood. The German command now began to switch their forces against Rennenkampf.

French gunners receiving instruction.

Far away to the south, on the other side of the vast salient where Russian Poland jutted westwards between East Prussia and Austria, Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austrian Chief of Staff, had been attacking to; driving up from eastern Galicia towards Lublin in the hope of cutting Russian communications. The force spread out along a 175-mile front. At Krasnik on 23-26 August and Komarow on the 26th the Austrians won encouraging successes.

So as the last days of August spun away in a roar of gunfire and an anguish of fatigue and exhaustion, the Allied armies were foundering back on both Eastern and Western Fronts. The war moved towards a climax.

On General Joseph Jacques Cesaire Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, the pressures were crushing. His own plans had collapsed; his impressionable traps were dismayed and discouraged by seemingly endless retreating ; his liaison officer with the BEF told him - wrongly - that the British had shot their bolt. Yet Joffre, a man as massive in character as in build, did not buckle. Realizing now the full shape and purpose of the Schlieffen Plan, he ordered the formation of a new army, the Sixth, under General Michel Maunoury, to the west of the BEF, and began sending troops by rail from his now quiescent right wing in Lorraine to his ever more endangered left.

Belgian soldiers during the defence of Louvain

before the Germans set the city ablaze on 25 August 1914.

In spite of their relentless forward marching all was not well on the German side. The Schlieffen Plan was proving too grandiose for available communications to sustain. Shrewd demolition of key railway tunnels by the Belgians had created crippling bottlenecks. Starved of reinforcements, the German armies could no longer man the extended front demanded by the Plan. Gaps opened between them. On 29 August General Lanrezac's Fifth French army exploited such a gap to drive Karl von Bülow's Second Army back across the Oise at Guise. Even though the setback was temporary, it caused Kluck to swing inwards to help Bülow. Kluck's new southeasterly axis of advance would take him to the east of Paris instead of the west as called for by the Schlieffen Plan. The shortage of men was forcing all the German armies to close up on each other; Kluck's change of direction would have been inevitable sooner or later.

Still the Germans came on under a blazing August sun, boots worn through, men swaying with fatigue; still the flies were going back and back, and the kilometric on the signposts to Paris shrank. On 2 September the French Government left Paris for Bordeaux; nevertheless, the Paris fortress commander General Joseph Gallieni, had orders to defend the city stone by stone. Next day Kluck's First Army and Bülow's Second crossed the Marne heading southeast; Kluck's right flank, the end of the German line, passing east of the Paris fortress area. Kluck's position and direction of march were observed and reported by British and French aircraft. On 4 September both Moltke, poring over his maps in his new headquarters in Luxembourg, and Joffre, sitting astride a hard chair in the dusty yard of a school at Bar-sur-Aube that now housed his headquarters, read the strategic situation alike. The German armies, far from outranking the Allies as intended by Schlieffen, had now exposed their own flank. At 10 p.m. that evening Joffre issued his order for an Allied counter-offensive to begin on 6 September.

German troops marching, with resting Austro-Hungarian troops looking on,

at the Eastern Front during August 1914.